Data Types, Variables, Operators#

Let’s kick things off by learning Mojo’s data types, variables and operators.

Data#

In simple words, Data refers to any information that is consumed by Intelligence. Computers store data in forms of numbers, text, images, audio, videos that can be stored and used by a program. Data is typically stored in variables, data structures, or files, and it is the fundamental building block for performing computations and creating meaningful output in a program.

for example -

name = "Amit Shukla"

🔥 = "Amit Shukla"

# in this case, instead of using an obvious identity such as << name >>,

# you can use any unicode char or even an emoji to store value of an object.

x = 1

# name = "Barbie"

# song = "what_was_i_made_for.mp3"

movie = "Barbie.mp4"

addresses = ["Malibu","Brooklyn"]

zipcode = ("90265","11203")

print(x)

## uncomment following to see error

# zipcode = ("90265","11203") # errors out

# addresses = [

{"City": "Malibu", zipcode: "90265"},

{"City": "Brooklyn", zipcode: "11203"}

]

## we will fix these errors later once we discuss variables

## uncomment following to see error

# x = 1

# name = "Barbie"

# song = "what_was_i_made_for.mp3"

# movie = "Barbie.mp4"

# addresses = ["Malibu","Brooklyn"]

# zipcode = ["90265","11203"]

# print(name, song, zipcode)

## we will fix these errors later once we discuss variables

# show case data types

# data type | data structure

a = 1

print("type of var a:",type(a))

b = 1.0

print("type of var b:",type(b))

c = "Hello World"

print("type of var c:",type(c))

d = (1,2)

print("type of var d:",type(d))

e = ["CA","OR"]

print("type of var e:",type(e))

f = {"a":1, "b":2}

print("type of var f:",type(f))

from collections import namedtuple

Tbl = namedtuple("col", ["x", "y"])

print("type of var d:", type(Tbl))

t = Tbl(x=1, y =2)

print("type of var t:", type(t))

print(t)

loc = ["CA","WA"]

print("type of var loc:", type(loc))

%%python

addresses = [

[{"City": "Malibu", "zipcode": "90265"}],

[{"City": "Brooklyn", "zipcode": "11203"}]

]

addresses = ("Malibu","Brooklyn")

print(addresses)

# above code just works fine, because it's python code.

Value Semantics#

Value Semantics is a concept in Computer Science that focuses on the value of an object rather that it’s identity.

Mojo enables users to utilize value semantics, allowing them to pass values (such as data structures like lists, arrays, strings, etc.) as logical copies rather than references.

Data Type#

Data Type is nothing but a classification of data, that tells compiler how program should process and use the data. It defines the type of value|data, a variable can hold and the type of operations can be performed on that value without causing errors.

For instance, adding two whole numbers is similar to adding two decimal numbers or adding a decimal number with a whole number. However, adding two pieces of text or two lists is quite different from adding numbers.

Understanding data types is crucial because it allows computers to perform faster. It’s important for the computer to know the context and type of data it is dealing with before running operations on that data. This helps ensure that the operations are performed correctly and efficiently.

In dynamic programming languages, programmers don’t always have to worry about data type conversions and can rely on the language to handle it. However, in static programming languages, it is appreciated to declare/annotate data types in advance. This may require a bit more code and reduce flexibility, but it greatly improves performance.

Many programming languages are capable of understanding data types based on their values, even if the programmer forgets to explicitly annotate the data type. This is known as “data type inference.”

Computer memory#

Before we move on to reviewing Python and Mojo code we write in previous section, let’s take a moment to understand the structure of computer memory. While it may seem overwhelming and unnecessary for Python and application programmers, trust me, having a basic understanding of computer memory systems can greatly benefit you as an AI Engineer when deploying your code.

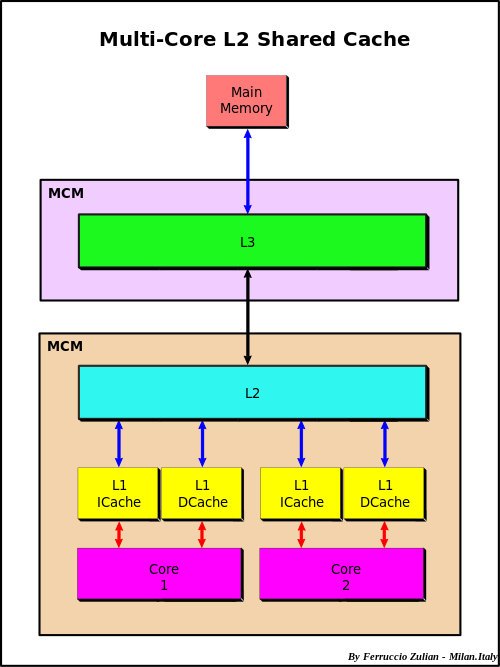

Credit: reference Dr. Chris Rackauckas At the highest level you have a CPU’s core memory which directly accesses a L1 cache. The L1 cache has the fastest access, so things which will be needed soon are kept there. However, it is filled from the L2 cache, which itself is filled from the L3 cache, which is filled from the main memory. This bring us to the first idea in optimizing code: using things that are already in a closer cache can help the code run faster because it doesn’t have to be queried for and moved up this chain.

When something needs to be pulled directly from main memory this is known as a cache miss

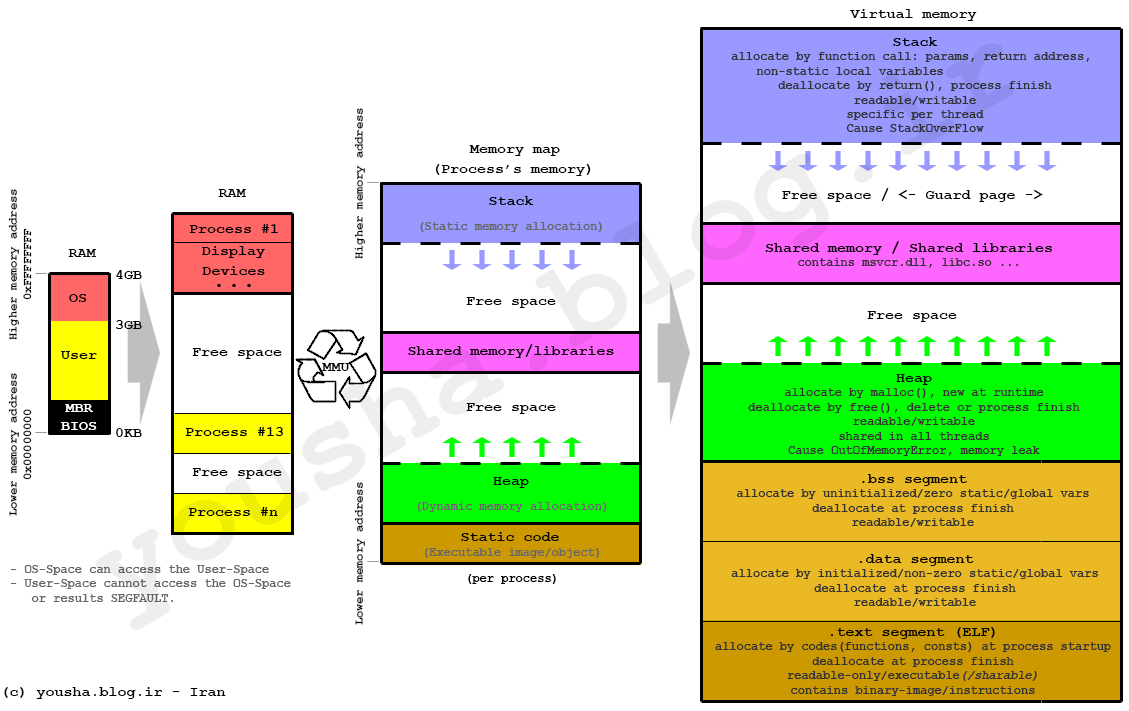

Lower Level View: The Stack and the Heap#

Locally, the stack is composed of a stack and a heap. The stack requires a static allocation: it is ordered. Because it’s ordered, it is very clear where things are in the stack, and therefore accesses are very quick (think instantaneous). However, because this is static, it requires that the size of the variables is known at compile time (to determine all of the variable locations). Since that is not possible with all variables, there exists the heap. The heap is essentially a stack of pointers to objects in memory. When heap variables are needed, their values are pulled up the cache chain and accessed.

Heap Allocations and Speed#

Heap allocations are costly because they involve this pointer indirection, so stack allocation should be done when sensible (it’s not helpful for really large arrays, but for small values like scalars it’s essential!)

Variables and Constants#

Now is the time to review Python and Mojo code we write in previous section.

Mojo provides different ways to declare variables. The var keyword allows you to create a mutable variable, while the let keyword allows you to create a variable that holds an immutable value.

Let’s re-run Mojo code.

x = 1

# uncomment and run to see error

# x = 2

let x = 1

# uncomment and run to see error

# x = 2

var x = 1

x = 2 # works fine

var name = "Amit"

name = "Amit Shukla"

let song = "what_am_i_made_of.mp3"

let movie = "Barbie.mp4"

let addresses = ["Malibu","Brooklyn"]

let zipcode = ("90265","11203")

Standard Data Types#

Warning

Mojo is a relatively new programming language, it is important to expect frequent changes and updates.

Before we dive into discussing Mojo’s standard data types, it’s important to understand that Mojo offers a wide range of built-in functionality through modules. Think of modules as libraries that contain various functionalities, such as data types, data structures and data methods, bundled together to serve a specific purpose. We will explore modules and packages in more detail later on.

Since these built-in modules are part of standard library, you don’t need to explicitly import them.

In Mojo, mostly a Type comes from a module’s struct implementation.

For example - Int is a type represents an integer value. It comes from int module that implements Int class.

If you explore the int module documentation in Mojo, you will notice that it provides a wide range of functionality for working with integer data types. This module allows you to perform multiple operations on integer values efficiently.

Mojo is a high-level programming language with an extensive set of modern features. Mojo also provides you, the programmer, access to all of the low-level primitives that you need to write powerful – yet zero-cost – abstractions.

In simpler terms, Mojo allows you to use existing or create your own data types and functionalities with zero-cost abstractions. Unlike other programming languages that bury data types deep within the compiler or language design, Mojo allows you to see through and define your own data types.

All the “standard types” (like Int, Bool, String and even Tuple) are made using struct.

let x: Int = 4

print(x)

let y: Int = 6

print(y)

# what it means, I declared two Immutable variables named `x` and `y`

# which hold a Integer data type, of size 64-bit on Stack memory.

# since, x is of type Int, which implement Int class from `int` module

# I can freely use methods __xxx__ defined on int module

# These __ aka "double underscore -> dunder -> magic functions" define most of primitive operations

TODO:::::::::::::::::::::::

print(x.__bool__())

print(x.__le__(y)) # same as x < y

Now that we have a grasp of what a data type is and how it is represented in computer memory, let’s explore some more examples of these data types.

Int

Bool

StringLiteral

String

FloatLiteral

ListLiteral

Dynamic Vectors

Tuple

Builtins

Utils

Slice

DTYPE

SIMD

Python

TODO:::::::::::::::::::::::

x = 1

name = "Amit Shukla"

song = "what_am_i_made_of.mp3"

movie = "Barbie.mp4"

addresses = ["Malibu","Brooklyn"]

zipcode = ("90265","11203")

print(x)

## uncomment following to see error

# zipcode = ("90265","11203") # errors out

# addresses = [

{"City": "Malibu", zipcode: "90265"},

{"City": "Brooklyn", zipcode: "11203"}

]

## we will fix these errors later once we discuss variables

## uncomment following to see error

# x = 1

# name = "Amit Shukla"

# song = "what_am_i_made_of.mp3"

# movie = "Barbie.mp4"

# addresses = ["Malibu","Brooklyn"]

# zipcode = ["90265","11203"]

# print(name, song, zipcode)

## we will fix these errors later once we discuss variables

StringLiteral, String#

TODO:::::::::::::::::::::::

var name = "Amit Shukla"

name = 3 # crash this variable to see error, it indicates, when a string variables is declared, Mojo compiler infer data type as StringLiteral

# var name = "Amit Shukla" << is equal to >> var name: StringLiteral = "Amit Shukla"

# String Literal is different than String,

# String is a pointer to heap allocated data and allows developer to store huge amount of data into it

# In Mojo the heap allocated String isn't imported by default:

from String import String

s = String("Mojo🔥")

print(s)

x = s.buffer

x = 20 # crash this to see data type

Copied!

error: Expression [17]:22:10: cannot implicitly convert ‘DynamicVector[SIMD[si8, 1]]’ value to ‘PythonObject’ in assignment x = s.buffer ~^~~~~~~

DynamicVector is similar to a Python list, here it’s storing multiple int8’s that represent the characters, let’s print the first character:

print(s[0])

Copied!

The other string type is a StringLiteral, it’s written directly into the binary, when the program starts it’s loaded into read-only memory, which means it’s constant and lives for the duration of the program:

var lit = “This is my StringLiteral” print(lit)

Copied!

This is my StringLiteral

Force an error to see the type:

lit = 20

Copied!

error: Expression [26]:26:11: cannot implicitly convert ‘Int’ value to ‘StringLiteral’ in assignment lit = 20 ^~

One thing to be aware of is that an emoji is actually four bytes, so we need a slice of 4 to have it print correctly:

emoji = String(”🔥😀”) print(“fire:”, emoji[0:4]) print(“smiley:”, emoji[4:8])

Copied!

fire: 🔥 smiley: 😀

Check out Maxim Zaks Blog post

for more details.

FloatLiteral#

Now lets take a look at the decimal representation:

from String import ord

print(ord(s[0]))

Copied!

77

That’s the ASCII code shown in this table

FloatLiteral

let float: FloatLiteral = 3.3 print(float)

Copied!

3.2999999999999998

let f32 = Float32(float) print(f32)

Copied!

3.2999999523162842

ListLiteral#

ListLiteral

When you initialize the list the types can be inferred, however when retrieving an item you need to provide the type as a parameter:

let list: ListLiteral[Int, FloatLiteral, StringLiteral] = [1, 5.0, “Mojo🔥”] print(list.get2, StringLiteral)

Copied!

Dynamic Vectors#

We can build our own string this way, we can put in 78 which is N and 79 which is O

from Vector import DynamicVector

let vec = DynamicVectorInt8

vec.push_back(78) vec.push_back(79)

Copied!

We can use a StringRef to get a pointer to the same location in memory, but with the methods required to output the numbers as text:

from Pointer import DTypePointer from DType import DType

let vec_str_ref = StringRef(DTypePointerDType.int8.address, vec.size) print(vec_str_ref)

Copied!

NO

Because it points to the same location in heap memory, changing the original vector will also change the value retrieved by the reference:

vec[1] = 78 print(vec_str_ref)

Copied!

NN

Create a deep copy of the String and allocate it to the heap:

from String import String let vec_str = String(vec_str_ref)

print(vec_str)

Copied!

NN

Now we’ve made a copy of the data to a new location in heap memory, we can modify the original and it won’t effect our copy:

vec[0] = 65 vec[1] = 65 print(vec_str)

Copied!

NN

Tuple#

Tuple

let tup = (1, “Mojo”, 3) print(tup.get0, Int)

Copied!

1

Builtins#

Utils#

These are all of the other builtin types not discussed which are accessible without importing anything, the type can be inferred, but are explicit here for demonstration, for example let bool: Bool = True can just be let bool = True: Bool

Standard Bool type

let bool: Bool = True print(bool == False)

Copied!

False

Int

Int is the same size as your architecture e.g. on a 64 bit machine it’s 64 bits

let i: Int = 2 print(i)

Copied!

2

It can also be used as an index:

var vec_2 = DynamicVectorInt vec_2.push_back(2) vec_2.push_back(4) vec_2.push_back(6)

print(vec_2[i])

Copied!

6

Slice#

A slice follows the python convention of:

start:end:step

So for example using Python syntax:

let original = String(“MojoDojo”) print(original[0:4])

Copied!

Mojo

You can also represent as:

let slice_expression = slice(0, 4)

print(original[slice_expression])

Copied!

Mojo

And to get every second letter:

print(original[0:4:2])

Copied!

Mj

Or:

let slice_expression = slice(0, 4, 2) print(original[slice_expression])

Copied!

Mj

Error

The error type is very simplistic, we’ll go into more details on errors in a later chapter:

def return_error(): raise Error(“This returns an Error type”)

return_error()

Copied!

Error: This returns an Error type

Before we conclude this topic, let’s discuss the SIMD data type, as it is an important concept to understand.

TOD:::::::::::: SIMD stands for Single Instruction, Multiple Data, hardware now contains special registers that allow you do the same operation across a vector in a single instruction, greatly improving performance, let’s take a look:

from DType import DType

y = SIMD[DType.uint8, 4](1, 2, 3, 4) print(y)

n the definition [DType.uint8, 4] are known as parameters which means they must be compile-time known, while (1, 2, 3, 4) are the arguments which can be compile-time or runtime known.

For example user input or data retrieved from an API is runtime known, and so can’t be used as a parameter during the compilation process.

In other languages argument and parameter often mean the same thing, in Mojo it’s a very important distinction.

This is now a vector of 8 bit numbers that are packed into 32 bits, we can perform a single instruction across all of it instead of 4 separate instructions:

y *= 10 print(y)

CS Fundamentals

Binary is how your computer stores memory, with each bit representing a 0 or 1. Memory is typically byte addressable, meaning that each unique memory address points to one byte, which consists of 8 bits.

This is how the first 4 digits in a uint8 are represented in hardware:

1 = 00000001

2 = 00000010

3 = 00000011

4 = 00000100

Binary 1 and 0 represents ON or OFF indicating an electrical charge in the tiny circuits of your computer.

Check this video if you want more information on binary.

We’re packing the data together with SIMD on the stack so it can be passed into a SIMD register like this:

00000001 00000010 00000011 00000100

The SIMD register in modern CPU’s is huge, let’s see how big it is in the Mojo playground:

from TargetInfo import simdbitwidth print(simdbitwidth()) 512

That means we could pack 64 x 8bit numbers together and perform a calculation on all of it with a single instruction.

You can also initialize SIMD with a single argument:

z = SIMDDType.uint8, 4 print(z)

Scalars:#

Scalar just means a single value, you’ll notice in Mojo all the numerics are SIMD scalars: var x = UInt8(1) x = “will cause an error”

error: Expression [14]:20:9: cannot implicitly convert ‘StringLiteral’ value to ‘SIMD[ui8, 1]’ in assignment x = “will cause an error” ^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

UInt8 is just an alias for SIMD[DType.uint8, 1], you can see all the numeric SIMD types imported by default here

Float16

Float32

Float64

Int8

Int16

Int32

Int64

UInt8

UInt16

UInt32

UInt64

Also notice when we try and change the type it throws an error, this is because Mojo is strongly typed

If we use existing Python modules, it will give us back a PythonObject that behaves the same loosely typed way as it does in Python:

np = Python.import_module(“numpy”)

arr = np.ndarray([5]) print(arr) arr = “this will work fine” print(arr)

Struct vs classes#

TODO::: You can build high-level abstractions for types (or “objects”) in a struct. A struct in Mojo is similar to a class in Python: they both support methods, fields, operator overloading, decorators for metaprogramming, etc. However, Mojo structs are completely static—they are bound at compile-time, so they do not allow dynamic dispatch or any runtime changes to the structure. (Mojo will also support classes in the future.)

struct MyPair: var first: Int var second: Int

fn __init__(inout self, first: Int, second: Int):

self.first = first

self.second = second

fn dump(self):

print(self.first, self.second)

let mine = MyPair(2, 4) mine.dump()

TODO::: write similar thing in Python

** will discuss argument ownership in details in later section